- 1. Finite, Countable, and Uncountable Sets

- 2. Metric Spaces

- 3. Compact Sets

- 4. Perfect Sets

- 5. Connected Sets

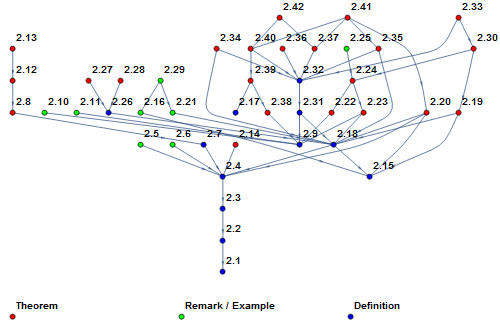

Dependencies

1. Finite, Countable, and Uncountable Sets

Definition 2.1: A function (or mapping) from the set $A$ to the set $B$ is a rule, $f$, which associates each $x\in A$ with some $f(x)\in B$. The set $A$ is called the domain of $f$. The elements $f(x)$ are called the values of $f$. The set of all values of $f$ is called the range of $f$.

Definition 2.2: Let $f$ be a function from the set $A$ to the set $B$. When $E\subset A$, $f(E)$ is defined to be ${f(x)\mid x\in E}$. We call $f(E)$ the image of $E$ under $f$.

The range of $f$ is $f(A)$. When $f(A) = B$ we say that $f$ is onto

If $E\subset B$ then $f^{-1}(E)$ is defined to be ${x\in A\mid f(x)\in E}$. We call $f^{-1}(E)$ the inverse image of $E$ under $f$. For each $y\in B$ we define $f^{-1}(y) = f^{-1}({y})$. If each $y\in B$ has the property that $f^{-1}(y)$ is a singleton set (i.e. has exactly one element). Then we say $f$ is a one-to-one (more briefly 1-1) function. In other words $f$ is 1-1 provided that the following holds: if $x_1\neq x_2$ then $f(x_1)\neq f(x_2)$.

Definition 2.3: If there is a function from $A$ to $B$ that is both 1-1 and onto, then we say $A$ and $B$ can be put in 1-1 correspondence, or that $A$ and $B$ have the same cardinal number, or that $A$ and $B$ are equivalent. Symbolically, we denote this by writing $A\sim B$. The relation $\sim$ has three important properties, which together make it an equivalence relation.

- Reflexive: For any set $A$, $A\sim A$.

- Symmetric: If $A\sim B$, then $B\sim A$.

- Transitive: If $A\sim B$ and $B\sim C$, then $A\sim C$.

Definition 2.4: Let $n\in\mathbb{Z}^{+}$ and let $J_n = {1,2,\dots, n}$ (so $J_1 = {1}$, and by convention $J_0 = \emptyset$). Let $J = \mathbb{Z}^{+}$. For any set $A$ we say:

- $A$ is finite if $A$ is empty or $A\sim J_n$ for some $n\in J$.

- $A$ is infinite if it is not the case that $A$ is finite.

- $A$ is countable if $A\sim J$.

- $A$ is uncountable if $A$ is neither finite nor countable.

- $A$ is at most countable if $A$ is either finite or countable (i.e. when $A$ is not uncountable).

If $A$ is finite, then $A$ cannot be equivalent to one of its proper subsets. However, if $A$ is infinite this is quite possible. For example $\mathbb{Z}^{+}\sim\mathbb{N}\sim\mathbb{Z}$.

Definition 2.7 A sequence is a function with domain $\mathbb{Z}^{+}$. Where $f(n)=x_n$ we usually denote the sequence by ${x_n}$ or by $x_1,x_2,x_3,\dots$. The values of $f$ are called terms. If $x_n\in A$ for each $n\in \mathbb{Z}^{+}$, then we say that ${x_n}$ is a sequence in $A$.

It is sometimes more convenient to start the terms of a sequence with $x_0$ instead of $x_1$. Any countable set, $A$, can be “arranged in a sequence” by finding a 1-1 and onto function from $\mathbb{Z}^{+}$ to $A$.

Theorem 2.8: Every infinite subset of a countable set is countable.

By the previous theorem, we can say that countable sets represent the “smallest” kind of infinity.

Definition 2.9: Let $A$ and $\Omega$ be sets. Suppose that each $\alpha\in A$ is associated with some $E_\alpha \subset\omega$. The set of all such $E_\alpha$ will be denoted ${E_\alpha}$ and is sometimes called a collection or family of sets. The union of ${E_\alpha}$ is the set $S$ where $x\in S$ if and only if $x\in E_\alpha$ for some $\alpha\in A$. The intersection of ${E_\alpha}$ is the set $P$ where $x\in P$ if and only if $x\in E_\alpha$ for every $\alpha\in A$. The notations for union and intersection follow.

There are some variations on these notations found in your book, with which you should also familiarize yourself.

Remarks 2.11: Union and intersection are commutative, associative, and distributive. We state these for intersection, but all statements are still true when intersection and union are interchanged.

- Commutative: $A\cap B = B\cap A$

- Associative: $(A\cap B)\cap C = A\cap (B\cap C) = A\cap B\cap C$

- Distributive: $A\cap (B\cap C) = (A\cap B) \cap (A\cap C)$

- Distributive: $A\cap (B\cup C) = (A\cap B) \cup (A\cap C)$

A few more properties of intersection and union follow.

- $A\subset A\cup B$

- $A\cap B\subset A$

- $A\cup \emptyset = A$

- $A\cap \emptyset = \emptyset$

- If $A\subset B$, then $A\cup B = B$ and $A\cap B = A$.

Theorem 2.12: A countable union of (at most) countable sets is (at most) countable.

Theorem 2.13: Let $A$ be countable and $B_n$ be the set of all $n$-tuples from $A$. Then $B_n$ is also countable.

Corollary: The set $\mathbb{Q}$ is countable.

Theorem 2.14: Let $A$ be the set of sequences in ${0,1}$. Then $A$ is uncountable. The proof of this theorem is very important. Make sure you understand it thoroughly. Proof: By way of contradiction, assume that $A$ is countable. Then for each $n$ there is a sequence $s_n$ in ${0,1}$, and every sequence in ${0,1}$ is equal to $s_n$ for some $n$. Consider the following sequence ${x_n}$. We define the term $x_n$ to be equal to $1$ if the $n^\text{th}$ digit of the sequence $s_n$ is $0$, and $0$ otherwise. In other words ${x_n}$ always differs from the sequence $s_n$ in the $n^\text{th}$ digit. But then ${x_n}$ is a sequence in ${0,1}$ which cannot be equal to any $s_n$. This is a contradiction.

2. Metric Spaces

Definition 2.15: A set $X$, whose elements we shall call points, is said to be a metric space if there is a distance between any two points $p$ and $q$, denoted $d(p,q)$ (disatnces are always taken to be real numbers). The distance function (AKA metric), $d$, must satisfy the following.

- $d(p,p) = 0$

- $d(p,q) > 0$ when $p\neq q$

- $d(p,q) = d(q,p)$

- for each $r\in x$, $d(p,q) \leq d(p,r) + d(r,q)$

The euclidean spaces, $\mathbb{R}^k$, (including $\mathbb{R}$ and $\mathbb{C}$) are all metric spaces under the metric $d(\vec{x},\vec{y})=\vert \vec{x} - \vec{y} \vert$. Any subset of a metric space is also a metric space using the same distance function.

Definition 2.17: The segment, $(a,b)$, is the set ${x\mid a<x<b}$ and the interval, $[a,b]$ is the set ${x\mid a\leq x\leq b}$.

Segments are still valid subsets of $\mathbb{R}$ when $a=-\infty$ or $b=+\infty$. It is also possible to consider the half-open intervals $[a,b)$ and $(a,b]$.

If, for each $i=1,\dots,k$, we have $a_i<b_i$, then the set of all points $\vec{x}\in\mathbb{R}^k$ whose coordinates satisfy $a_i<x_i<b_i$ is called a $k$-cell. (Thus a $1$-cell is an interval, a $2$-cell is a rectangle, and a $3$-cell is a box.)

If $\vec{x}\in\mathbb{R}^k$ and $r>0$ then the open (or closed) ball, $B$ centered at $\vec{x}$ with radius $r$ is the set of all $\vec{y}\in\mathbb{R}^k$ such that $\vert\vec{y}-\vec{x}\vert<r$ (or $\vert\vec{y}-\vec{x}\vert\leq r$).

The set $E\subset\mathbb{R}^k$ is called convex if

whenever $\vec{x},\vec{y}\in E$ and $0<\lambda<1$.

Balls (open or closed) and $k$-cells are both examples of convex sets.

Definition 2.18: Let $X$ be a metric space.

- A neighborhood of $p\in X$ is a set $N_r(p)$ consisting of all points $q\in X$ such that $d(p,q)<r$. The real number $r$ is called the radius of $N_r(p)$.

- A point, $p\in X$, is a limit point of the set $E$ if every neighborhood of $p$ contains a point $q\neq p$ such that $q\in E$.

- If $p\in E$ and $p$ is not a limit point of $E$, the $p$ is called an isolated point of $E$.

- A set $E$ is called closed when each limit point of $E$ is also an element of $E$.

- A point $p$ is an interior point of $E$ if there is a neighborhood of $p$ which is contained in $E$.

- A set $E$ is called open when each point of $E$ is an interior point of $E$.

- The complement of $E$ is $E^c$, which denotes the set of all $p\in X$ such that $p\notin E$.

- A set $E$ is called perfect if $E$ is closed and every point of $E$ is also a limit point of $E$.

- A set $E$ is called bounded if there is a real number, $M$, and a point $q\in X$ such that $d(p,q)<M$ for every $p\in E$.

- A set $E$ is called dense in $X$ if every point of $X$ is a limit point of $E$, or a point of $E$, or both.

In $\mathbb{R}$, neighborhoods are segments. In $\mathbb{R}^2$ (or $\mathbb{C}$), neighborhoods are the interiors of circles. In $\mathbb{R}^3$, neighborhoods are the interiors of spheres.

Theorem 2.19: Every neighborhood is an open set.

Theorem 2.20: If $p$ is a limit point of $E$, then every neighborhood of $p$ contains infinitely many points of $E$.

Corollary: Finite sets have no limit points.

It might not be surprising to hear that there are sets which are neither open nor closed. Example 2.21 shows that there are sets which are both open and closed (we sometimes refer to these as clopen). You will also find several examples of the classification of sets as being perfect and/or bounded.

Theorem 2.22: Let ${E_\alpha}$ be a (finite or infinite) collection of sets. Then

A very similar proof shows that

Theorem 2.23: A set $E$ is open if and only if its complement is closed.

Corollary: A set $F$ is closed if and only if its complement is open.

Theorem 2.24:

- Any union of open sets is open.

- Any intersection of closed sets is closed.

- A finite intersection of open sets is open.

- A finite union of closed sets is closed.

An infinite intersection of open sets may or may not be open. An infinite union of closed sets may or may not be closed.

Definition 2.26: If $X$ is a metric space, $E\subset X$, and $E’$ is the set of all limit points of $E$ in $X$, then the closure of $E$ is $\overline{E}=E\cup E’$.

Theorem 2.27: Let $X$ be a metric space, and $E\subset X$. Then

- $\overline{E}$ is closed.

- $E = \overline{E}$ if and only if $E$ is closed.

- For each closed set $F$ in $X$ such that $E\subset F$, it must also be the case that $\overline{E}\subset F$.

Theorem 2.28 Let $E$ be a non-empty set of real numbers which is bounded above, and let $y=\sup E$. Then $y\in\overline{E}$.

Theorem 2.30 Suppose that $Y\subset X$. A subset $E$ of $Y$ is open relative to $Y$ if and only if $E = Y\cap G$ for some open subset $G$ of $X$.

In case we have two metric spaces $Y\subset X$, it is quite possible for $E$ to be open (or closed) in $Y$, but not open (or closed) in $X$. For example, consider $Y = \mathbb{R}$ and $X = \mathbb{C}$. Then the segment $E = (0,1)$ is open in $Y$, but not open in $X$.

3. Compact Sets

Definition 2.31: Let $E$ be a subset of the metric space $X$. Then the (possibly infinite) collection ${G_\alpha}$ is an open cover of $E$ when each $G_\alpha$ is open and $E\subset\bigcup_\alpha G_\alpha$.

Definition 2.32: Let $K$ be a subset of the metric space $X$. Then $K$ is said to be compact when every open cover of $K$ contains a finite sub-cover. More explicitly, if ${G_\alpha}$ is any open cover of $K$, then there are finitely many indices $\alpha_1,\dots,\alpha_n$ such that $K\subset G_{\alpha_1}\cup\dots\cup G_{\alpha_n}$.

For now it is only clear that any finite set is compact.

Theorem 2.33: Suppose that $K$ is a subset of the metric space $Y$, which is a subset of the metric space $X$. In symbols $K\subset X\subset Y$. Then $K$ is compact relative to $X$ if and only if $K$ is compact relative to $Y$.

Compare this to the remark about open and closed sets at the end of the previous section.

Theorem 2.34: Compact subsets of metric spaces are closed.

Theorem 2.35: Closed subsets of compact sets are compact.

Corollary: If $F$ is closed and $K$ is compact, then $F\cap K$ is compact.

Theorem 2.36: If ${K_\alpha}$ is a collection of compact subsets of the metric space $X$ such that the intersection of every finite subcollection of ${K_\alpha}$ is non-empty, then $\cap_\alpha K_\alpha$ is non-empty$.

Corrolary: If ${K_n}$ is a sequence of non-empty compact sets such that $K_{n+1}\subset K_n$, then $\bigcap_{n=1}^\infty K_n$ is non-empty.

Theorem 2.37: If $E$ is an infinite subset of a compact set $K$, then $E$ has a limit point in $K$.

Theorem 2.38: If ${I_n}$ is a sequence of intervals in $\mathbb{R}$ such that $I_{n+1}\subset I_n$, then $\bigcap_{n=1}^\infty I_n$ is non-empty.

Theorem 2.39: If ${I_n}$ is a sequence of $k$-cells in $\mathbb{R}^k$ such that $I_{n+1}\subset I_n$, then $\bigcap_{n=1}^\infty I_n$ is non-empty.

Theorem 2.40: Every $k$-cell is compact.

Theorem 2.41 (*The Heine-Borel Theorem): If a set $E$ in $\mathbb{R}^k$ has one of the following three properties, then it has the other two.

- $E$ is closed and bounded.

- $E$ is compact.

- Every infinite subset of $E$ has a limit point of $E$.

The latter two are equivalent in any metric space. However, it is not generally the case (outside of the very specific metric space $\mathbb{R}^k$) that being closed and bounded implies compactness.

Theorem 2.42: Every bounded infinite subset of $\mathbb{R}^k$ has a limit point in $\mathbb{R^k}$.

4. Perfect Sets

Testing 1, 2, 3. This is only a test.