- Section 6.1 - Areas Between Curves

- Section 6.2 - Volumes

- Section 6.3 - Volumes by Cylindrical Shells

- Section 6.4 - Work

- Section 6.5 - Average Value of a Function

Section 6.1 - Areas Between Curves

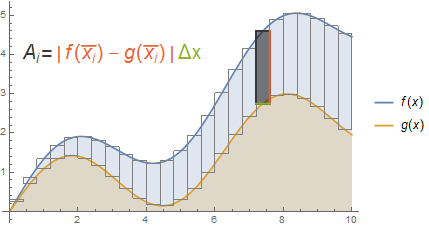

In the simplest case, we have $0\leq g(x)\leq f(x)$ on the interval $(a,b)$. Then the area between the curves $y=g(x)$, $y=f(x)$, $x=a$, and $x=b$ is given by $\int_a^b (f(x)-g(x))\,dx$. This also works without the assumption that $0\leq f(x)$ because we can approximate the area with a Riemann sum by partitioning the interval $(a,b)$. The height of each rectangle will be $f(x_i)-g(x_i)$ and so $A_i = (f(x_i)-g(x_i))\Delta x$, as depicted in the picture below. The total area is approximated as $\sum_{i=1}^n A_i$, and as $\Delta x\to 0$ (i.e. as $n\to\infty$), this Riemann sum turns into the integral previously described.

Integrating an absolute value

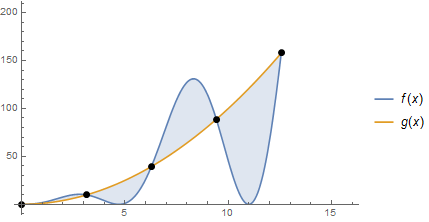

Often it is not the case that one function is larger than the other on the entire interval. In this case, the height of the rectangle is given by $\vert f(x_i)-g(x_i)\vert$. There is no shortcut for integrating $\int_a^b\vert f(x)-g(x)\vert\,dx$. We have to break up $(a,b)$ into all the intervals where $f(x)\leq g(x)$ and all the intervals where $g(x)\leq f(x)$. This can be done by solving $f(x)=g(x)$ and either (a) making a sign chart, or (b) looking at the graph. See the figure below.

In the above, $a=0$, $b=4\pi$, $f(x)=x^2\sin(x)$ and $g(x)=x^2$. Solving $f(x)=g(x)$ yields $x=0,\pi,2\pi,3\pi,4\pi$. So the area between the curves is given by:

Integrating along the $y$-axis

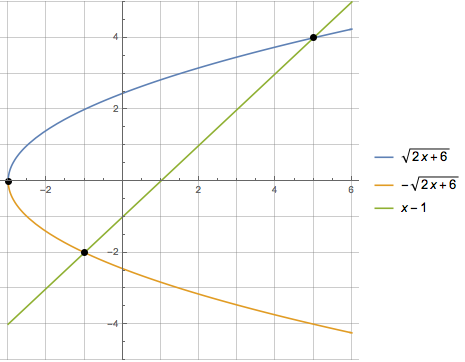

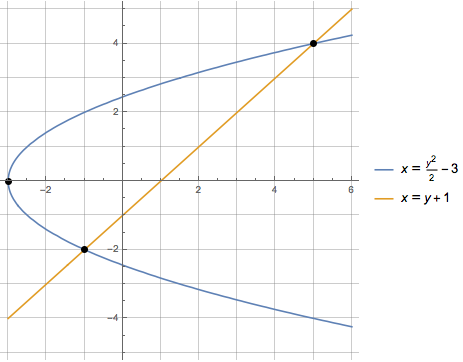

In some situations, a region is better described by considering $x$ as a function of $y$. Consider Example 6 from your book. We want to find the area enclosed by the line $y = x-1$ and the parabola $y^2 = 2x+6$.

We could set this integral up using $f(x) = \sqrt{2x+6}$, $g(x)=-\sqrt{2x+6}$ and $h(x)=x-1$.

The area bound by the curves is then given by:

But we can simplify the process by integrating along the $y$-axis instead of the $x$-axis.

Then the area bound by the curves is given by the much simpler integral:

Section 6.2 - Volumes

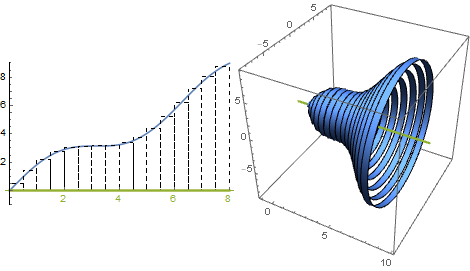

Revolving the region under a curve about the $x$-axis

Let $f(x) = x + \sin(x)$ and let $S$ be the region bound by $y=f(x)$, the $x$-axis, and $x=8$. We want to find the volume obtained by revolving $R$ about the $x$-axis.

Approximating the region with rectangles is a natural approach because when a rectangle is revolved about the $x$-axis it becomes a cylinder. We know the volume of a cylinder is $V = \pi r^2h$ where $r$ is the radius and $h$ is the height. In this case $r = f(x)$ and $h = \Delta x$. Thus, an approximation of the volume we seek is $\sum V_i = \sum \pi f\left(\overline{x_i}\right)^2 \Delta x$. As $\Delta x\to 0$ we find the exact volume to be

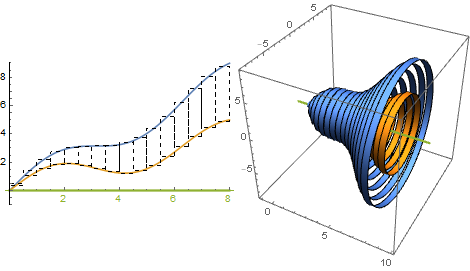

Revolving more complex regions about the $x$-axis

Now let $g(x) = x/2 + \sin(x)$ and let $S$ be the region bound by $y=f(x)$, $y=g(x)$, and $x=8$. We want the volume obtained by revolving $S$ about the $x$-axis.

The rectangles approximating the region $S$ do not touch the $x$-axis, so when we revolve them we get a washer instead of a solid cylinder. The volume of such a washer would be the volume of the outer cylinder minus the volume of the inner cylinder:

Here we have $R = f(x)$ and $r = g(x)$

Finally, summing and letting $\Delta x\to 0$ gives the integral:

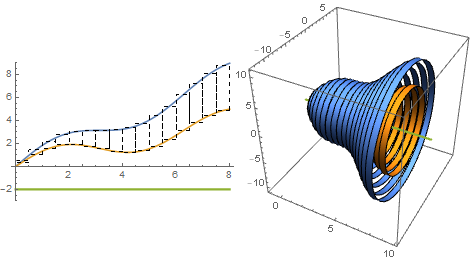

Revolving about arbitrary horizontal lines

Suppose now that we want to revolve the region $S$ about the line $y=-2$ instead of the $x$-axis (which has equation $y=0$).

Instead of $R = f(x)$, we now have $R = f(x) - (-2) = f(x) + 2$. Similarly, $r = g(x) + 2$. So the volume of the solid of revolution is given by the integral:

Revolving about vertical lines

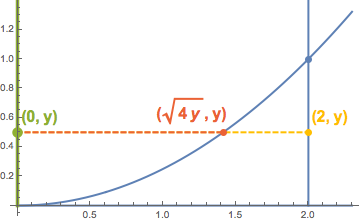

The key to keeping all this straight is that when using the method of slicing, we integrate along the axis of revolution. This gives us a radius perpendicular to the axis of revolution (as the radius of a cylinder runs perpendicular to its height). For example consider the region, $S$, bound by $y=\frac14 x^2$, $x=2$, and $y=0$. Let’s find the volume obtained by revolving $S$ about the $y$-axis.

The cross-sections are washers with $R=2$ and $r=\sqrt{4y}$. We obtained our formula for $r$ by solving $y=\frac14 x^2$ for $y$. Now we can set up our integral. Observe that the smallest $y$-coordinate in the region $S$ is $0$ and the largest is $\frac14 (2^2)=1$. These give us our limits of integration.

General volumes

The method of slicing can be used to find volumes of regions that aren’t necessarily obtained by revolving a region about a line. In fact, it applies to any region and any axis. All we need to be able to do is associate with each point, $p$, along that axis, a cross-sectional area, $A(p)$. (This is easiest to picture when the axis is either horizontal or vertical with respect to the $xy$-plane, i.e. when $p$ is either $x$ or $y$.) Once we know the cross-sectional areas, we can find the smallest and largest $p$-coordinates in the region and set up the integral: $\int_a^b A(p)\,dp$.

Section 6.3 - Volumes by Cylindrical Shells

In this section we will find volumes by integrating perpendicular to the axis of revolution. In some cases this can make the integral much easier to evaluate (not so much in others). Unlike the method of slicing, this method is only suited to finding the volume of a solid of revolution.

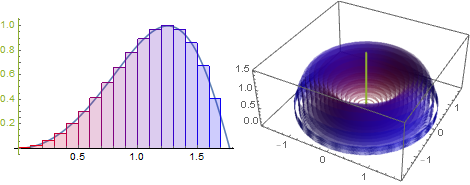

The picture below shows, on the left, the region bound by $y=\sin(x^2)$ and the $x$-axis, with $0\leq x\leq\pi$, approximated by rectangles. The axis of revolution in this case is the vertical line $x=0$ (the $y$-axis). On the right, we see the solid of revoution approximated by cylindric shells.

When one of these rectangles is revolved about the $y$-axis, we get a hollow cylinder (which we call a cylindric shell). The volume of one of these shells is given by:

where $R$ represents the outer radius of the shell, $r$ represents the inner radius, and $h$ represents the height. If the rectangle occupies $(x_i,x_{i+1})$ on the $x$-axis and has height $f\left(\overline{x_i}\right)$, then $r = x_i$, $R = x_{i+1} = x_i + \Delta x$, and $h = f\left(\overline{x_i}\right)$. So the volume of one of our shells could be expressed as:

Notice that $(x_i+\Delta x)^2 - x_i^2 = 2x_i\Delta x + \Delta x^2$. So summing and allowing $\Delta x\to 0$ we get the integral:

In the example above, $a=0$ and $b=\sqrt{pi}$. In all cases, these represent the inner-most and outer-most (respectively) coordinates running perpendicular to the axis of revolution. The astute observer will note that $2\pi r h$ (the quantity we integrated, where $r=x$ and $h=f(x)$) is exactly the area of a hollow cylinder with radius $r$ and height $h$!

If we wanted to revolve about $x=-1$ then we could use $r = x + 1$. If we wanted to revolve a region about the $x$-axis, then our radius would be measured vertically (instead of horizontally) and the height would be measured horizontally. We could even revolve a region bound between two curves by allowing the height to be, e.g. $h = f(x)-g(x)$.